Colonial Wars |

American Wars |

Link To This Page — Contact Us —

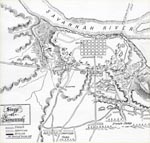

The Battle of Savannah

September 16, 1779 in Savannah, Georgia

|

||||||

|

The British easily captured Savannah from the Americans in early 1778. This set the stage for the second bloodiest battle of the Revolution.

Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, recently appointed Southern commander of the Continental Army, realized that the loss of Savannah was key and set out to regain the coastal Georgia port. His first task was to raise 5,000 men. Second, since raising a navy was out of the question, he tried to contact Adm. Valerie D'estaing, whose French fleet had been raiding British outposts in the Caribbean Sea. D'estaing's naval support, comprised of some 22 line ships, about half that many support ships and 4,000 men was the only way to ensure that British ships could not arrive to supply and support the town.

While Lincoln was preparing his troops, Revolutionary Georgia continued its organization of a government in exile. It was the loss of Savannah that woke the American government to the danger of losing the South. Washington, D.C. sent Gen. Casimir Pulaski and his "Polish Legion" to the southern front.

On both the left and right sides of Savannah, the marshes created tough obstacles through which to advance. In front, a cleared plain of small rolling hills made it impossible for a large group of men to advance without being seen from the redoubts that encircled the city. Defenses could be used by the British to protect themselves.

On September 1, D'estaing arrived east of Savannah. Had he been as bold as Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell had been less than a year earlier, he probably could have captured the city by himself. Instead, he formed a line and waited for the Continental Army. Gen. Augustine Prevost also set to work on the city's defenses, ordering boats grounded along the bank of the river, then manned defensively. He also ordered a group of 800 men under the command of Col. John Maitland in Beaufort, South Carolina to hold their position, but be ready to advance in support of the city if needed.

Lincoln left Charleston and joined Gen. Lachlan McIntosh at Ebenezer. From here, the Continental Army advanced and began to take position around the city.

With the arrival of the opposing force, Governor James Wright ordered able-bodied men to assist in building Savannah's defenses. Both Lincoln and D'estaing knew that the siege would not be long, for Britain would find out about the naval blockade and send enough ships to break through D'estaing's line. It was the belief of the American commanders that the British forces would surrender if their escape routes were cut.

On September 8, a French fleet of 42 ships with 4,000 soldiers aboard arrived off Tybee. American forces from Charleston, under Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, approached Savannah from the north. The British, believing the French fleet to be occupied in the Caribbean, were taken by surprise. With a garrison of about 700, Savannah was ripe for the taking but the allies waited, delaying an assault until the British garrison was reinforced by Col. John Maitland and the 71st Highlanders who had been at Beaufrot, South Carolina when the French arrived. Commanded by a cautious D'Estiang, the French shelled the city with little real effect.

During the 3-week bombardment a great deal of property was damaged. During one night of the bombardment, the French gunners were drunk and firing on their own men.

On September 16, Lincoln and D'estaing met at D'estaing's headquarters in Thunderbolt and work began on "completing the encirclement." D'estaing issued a surrender demand to Prevost. As Prevost considered the demand, his men worked feverishly on improving Savannah's defenses.

On September 23, Savannah was fully invested, although Prevost did call for the troops from Beaufort, who apparently got through the American line with little difficulty. The actual siege preparations were finally completed. For the next 2 weeks British troops, Loyalist Tories and Negro slaves continued to work on the defenses of Savannah while Benjamin Lincoln did little to improve his position.

By October 4, no progress had been made towards a British surrender, so D'estaing moved his ships into position and began a naval bombardment of the city. This did not deter the British, who continued their task of improving the city's defenses. Finally Lincoln and D'estaing agreed to attack the British positions across a broad front on October 9. D'estaing's plan called for 5 groups would move forward, concentrating on a salient in the British line at Spring Hill where a group of South Carolina militia appeared to be holding the line.

On October 9, at dawn, thousands of French and Americans attacked the British positions and were cut down. It was the bloodiest hour in the Revolutionary War. Pulaski and Marion expressed strong disagreement with the plan proposed by D'estaing, but obeyed orders. As the 5 units attacked the British resistance stiffened. Still, Continental soldiers broke through the redoubt in at least two places near Spring Hill. As the Americans carried the wall of the redoubt, the flags were planted to show the soldiers the breach in the line. Suddenly, British Regulars, under the command of Col. John Maitland, advanced and turned back the combined French and Continental Army.

The American line at the redoubt began to crumble under the intense pressure of Maitland's Regulars. Pulaski, seeing the line pull back, rode up and tried to rally the men as well when he was mortally wounded by cannister. American hero, Sgt. Jasper, was killed on the ramparts trying to save his unit's battle flag. Polish patriot Casimir Pulaski was killed in a calvary charge. Black troops from Haiti in the French reserve came forward to cover the retreat of the shattered attackers. In an hour, a thousand casulaities resulted. During a truce, hundreds of French and American soldiers were buried in a mass grave. The city was held by the British until 1782 although guerilla efforts by men like Col. Francis Marion, a survivor of the seige, continued.

After this battle, d'Estaing returned to France and Pulaski was taken to the USS Wasp and was buried at sea on October 15. Both the American and the French remained in the area until October 16, when Lincoln began an orderly withdrawal to Charleston.